Treatment for Guillain-Barré (GBS)

Treatment for GBS can help improve the symptoms and speed up recovery.

Most people need to stay in hospital for a few weeks to a few months. Usually either intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg) or plasma exchange is given if the person cannot walk unaided, or if symptoms are worsening rapidly.

Milder cases of GBS usually improve without these treatments.

In this section you’ll find information about treatments, what may happen in the ICU, and what Family and Friends Can Do To Help.

To skip to a specific section, just hit one of the headers below.

Plasma Exchange (Plasmapheresis)

Intensive Care | Advice for Friends and Family

Intensive Care | How Does a Ventilated GBS Patient Feel?

Intensive Care | Hallucinations

Intensive Care | Locked-In and Feeling Vulnerable

What Family & Friends Can Do To Help (WFFCDTH): Communication

Intravenous Immunoglobulin

The most commonly used treatment for Guillain-Barré syndrome is intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg). Immunoglobulin is made from donated blood that contains healthy antibodies which can help stop the harmful antibodies damaging your nerves. IVIg is given intravenously, which means directly into a vein, over a period of five days, and is most effective if given in the first two weeks following onset.

Plasma Exchange (Plasmapheresis)

Plasma exchange, also called plasmapheresis, is sometimes used instead of IVIg. This involves being attached to a machine that removes blood from a vein and filters out the harmful antibodies that are attacking your nerves before returning the blood to your body. This is also usually delivered over a period of five days, and is considered most effective during the first four weeks following onset.

Both IVIg and plasma exchange are considered to be equally effective and on average lead to earlier recovery than if left untreated. Unfortunately these treatments do not work for everyone. There are currently no other treatments with proven efficacy for GBS.

Specific Patient Groups

Patients with pure MFS tend to be more mildly affected than GBS, and most recover completely without treatment within a few months. Therefore, in pure MFS treatment is generally not recommended, but patients should be monitored and a subgroup may need treatment if they develop significant weakness (considered to be GBS-MFS overlap) or BBE.

Pregnant Women

Either IVIg or plasma exchange may be given during pregnancy if required. IVIg may be preferred.

Other Treatments

While in hospital, you’ll be closely monitored to check for any problems with your lungs, heart or other body functions. You may also be given treatment to relieve your symptoms and reduce the risk of further problems. This may include:

- a ventilator if you’re having difficulty breathing

- a feeding tube through your nose if you have swallowing problems

- painkillers if you’re in pain

- being gently moved around on a regular basis to avoid bed sores and keep your joints healthy

- a thin tube called a catheter in your urethra (the tube that carries urine out of the body) if you have difficulty peeing

- laxatives if you have constipation

- injections to prevent blood clots

- physiotherapy to help you learn to move again and build up your strength

Intensive Care | Advice for Friends and Family

Intensive care is a unit within hospitals, staffed by medical support personnel who are specially trained in the high levels of care required. This is also known as ITU (Intensive Therapy Unit). Patients are constantly monitored, day and night, and everything is done to ensure that they receive the highest level of care possible. The amount of equipment may seem a bit daunting at first, but you will soon become familiar with all the machinery.

Admission to ICU is particularly recommended for patients who are experiencing problems with their breathing, swallowing or coughing muscles. Around 20% of GBS patients are admitted to ICU.

Equipment that may be used on an ICU includes:

- ventilator – a machine that helps with breathing by pumping air in and out while they are temporarily unable to breath unaided.

- breathing tube – placed in the mouth, nose, or through a small cut in the throat (tracheostomy) which makes it more comfortable if ventilation is likely to be needed for longer than a week. This cut will heal up when the person can breathe again for themselves. The inflatable cuff around the bottom of this tube stops fluid and secretions from slipping down the throat into the lung and causing infection.

- monitoring equipment – used to measure important bodily functions, such as heart rate (ECG), blood pressure and the level of oxygen in the blood.

- IV lines and pumps – tubes inserted into a vein (intravenously, iv) to provide fluids, nutrition and medication

- feeding tube, placed through the nose down into the stomach (nasogastric tube, NGT) or sometimes through a small cut made in the tummy (gastrostomy, PEG) if a person is unable to eat normally

- catheter – a think tube to drain urine from the bladder

- drain – tube used to remove any build-up of blood or fluid from the body

Intensive Care | How Does a Ventilated GBS Patient Feel?

Some patients in ICU are fully awake, others are awake but partially sedated with medication to help them relax, and others are kept asleep. If awake, they may be alarmed at the new situation and surroundings, so talk to them calmly and explain what is going on.

Intensive Care | Senses

They may have reduced or absent sense of taste and smell, and some patients experience visual disturbance. Hearing is unlikely to be affected, and GBS does not affect the brain, so the patient is usually aware of what is going on around them. However, this may be dampened by sedative or painkilling drugs which are often used to make GBS patients more comfortable.

Some patients do experience an increase in skin sensitivity so although contact is important, be aware that rarely even a light touch may cause severe pain which the patient cannot easily communicate to you.

During the severe phase of the illness, GBS patients can feel very hot or cold and might frequently request a fan to be turned on and off.

Intensive Care | Movement

GBS is a paralysing condition. The paralysis is temporary but may be extensive, which can be frightening and hard for the patient to accept. Because of the lack of movement, there may be muscle wasting, possibly leading to weight loss. Gentle physiotherapy, even at the early stages, will help to minimise stiffness of joints and muscles. The nurses will regularly turn the patient to prevent bed sores.

Intensive Care | Pain

Pain is common in GBS and may be experienced to a greater or lesser degree at various sites around the body, for which appropriate medication will be given. Pain levels must always be considered when moving the patient and care taken to ensure that all movements are as gentle as possible.

Intensive Care | Hallucinations

Hallucinations, unusually vivid daydreams or nightmares are not uncommon for GBS patients when very weak. They may be worsened by sedative or painkilling drugs but can also arise in patients without any drug effects. They are not necessarily frightening, but hallucinations can seem very real, and they may be convinced that these are actual events. Talk to them calmly, using their name, and ask them what is happening, and whether they feel afraid or confused. Explain that they are having a hallucination and that you don’t see or hear what they do, but acknowledge their feelings. Tell them you are there, and everything is ok. Gentle patting may help bring them back, and you could try to turn their attention to something they enjoy, by talking about favourite music or a TV programme they like to watch.

Intensive Care | Locked-In and Feeling Vulnerable

Many GBS patients are alert and acutely aware of what is going on. They feel vulnerable, isolated and locked-up inside their own body. They are likely to feel anxious and frustrated and may exhibit irrational or uncharacteristic behaviour. It will be difficult to come to terms with what has happened, so do not be surprised if they are tearful, bad tempered or panicky.

Mentally and emotionally, loss of movement and inability to speak makes a person feel fragile and vulnerable, so be sympathetic and caring whenever you are with them.

What Family & Friends Can Do To Help (WFFCDTH): Communication

Understand as much as you can about this condition. If you are the person visiting most frequently, introduce yourself to the doctor in charge of the case and don’t be afraid to ask questions. Some doctors are better than others at explaining things, so let them know if you don’t understand. Get to know the regular nursing staff and ask for a daily update on progress.

Physiotherapy can start while the patient is still paralysed. Get to know the physio and keep yourself updated on procedure and progress. They can tell you how you can help with exercises between physio sessions.

Talk to the speech therapist about communication aids. If facial muscles aren’t paralysed, then lip reading could help. Some people retain finger movement and can write letters in the air or on the palm of the hand. A common method of communication with a patient whose movements are restricted to the eyes and eyelids, is to use a question and answer technique with the patient answering with one blink for ‘yes’ and two for ‘no’. Pointing to the letters on an alphabet board and asking ‘Is it on this line? Is this the letter?’, will help. If the patient is strong enough, they may be able to point at an alphabet board with a finger or pointer attached to a headband.

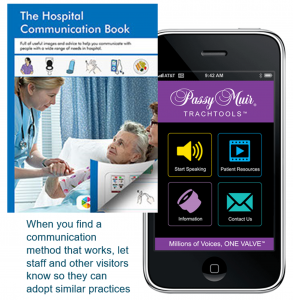

A hospital communication book contains lots of words and images useful in a hospital setting and can pre-empt many questions or comments a ventilated patient is likely to make. GAIN will send you a free copy on request, that you can leave at the bedside for staff and visitors to use.

Another useful tool is an app developed by David Muir, who was ventilated due to muscular dystrophy and became non-verbal as a result.

The app is called Passy Muir Trachtools and is free to download in your app store for Apple and android devices.

It has several pre-recorded phrases, and allows you to record your own customized words and messages. When you find a communication method that works, make sure you share this with staff and other visitors so they can adopt the same practice.

WFFCDTH: Mental Stimulation

Remember they are socially isolated and will need to be stimulated. Tell them what day it is and talk about what is happening in the outside world. Read extracts from the news and encourage friends and family to send cards and texts about what they are up to. Remember to include them in all conversations, even if they can’t respond verbally.

Make use of your tech! Read to them or offer to play an audio book on their smartphone or tablet. Download films, favourite TV shows and music onto their device and watch or listen together if you can, with one earbud each.

WFFCDTH: Financial Worries

Financial concerns may be causing anxiety, especially if the patient is the main wage-earner. Get in touch with the Social Worker at the hospital who will advise on benefits. Alternatively, Citizens’ Advice offers free expert advice which you access online, or by phoning your local office. Stay in regular contact with employers and make sure you understand the absence and returning to work processes. There is more information about returning to work later in the booklet.

GAIN may be able to help through our Personal Grants Scheme with travel costs for frequent journeys visiting a family member in hospital.

WFFCDTH: Comfort

The little things you can do will mean a lot. Do they need a hair wash or a shave? Do nails need manicuring? Can you help by massaging their hands or feet? Eating and drinking while you’re visiting might have a negative impact, if they are unable to swallow anything, so make sure you have something before you arrive.

Some patients have pain in the acute stage, others as recovery kicks in, and some have no pain at all. Try to understand what pain they have, if any, and the frequency and type of medication being given to alleviate it.

GBS patients tire easily, may be on sedative drugs and may nap quite frequently. They might not want visitors over and above one or two close family members, especially in the early stages following diagnosis and the start of recovery.

At the end of your visit, make sure you leave them in the best possible frame of mind. Turn off any device that might cause irritation or disturbance and make sure they have what they need or can attract attention if required.

WFFCDTH: Coming Off The Ventilator

As things improve, they will be taken off the ventilator, often starting with just a few minutes and building up gradually. Patients can get quite panicky at the beginning of this procedure as they have become reliant on the ventilator and might not believe

that they can breathe again without it. Reassure them that their natural ability to breathe is returning and that this is the start of getting well.

Once off the ventilator, it is likely that they will soon be transferred to a general ward for a time before moving into a rehab unit or being discharged home. Moving out of ICU, where patients are monitored continuously, can be stressful in itself, but it’s all part of recovery, and no one will be moved until the medical team is satisfied that they are ready.

WFFCDTH: Stay Positive

Your role is to offer love, comfort and reassurance during this difficult period. Try to remain calm and positive and give lots of encouragement on progress. Keep yourself well informed by the medical staff. Writing a few lines each day in a journal will help you keep a perspective on progress. You can share this over the coming weeks to show how far they’ve come since those early days. For close family, this period of the illness can be an exhausting time of stress, uncertainty and disruption, as you struggle to maintain other commitments alongside frequent hospital visits, so don’t forget to look after yourself and stay well. If it is difficult for you to visit as frequently as you would like, we might be able to help you keep in touch with a smart tablet. Contact GAIN for further details.

Welcome to our Guillain-Barré Syndrome Information Hub.

Here we breakdown what is happening to you or a loved in simple but proper terms. Our information is sourced from our Medical Advisory Board, medical texts, and recognised support providers.

If you have any questions after reading this that you feel haven’t been answered. Please get in touch with us, we will strive to point you in the right direction.

What is Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) and the variants?

We discuss the basics of GBS – what it is, some of the symptoms you may experience, different types, symptom variants, Miller Fisher, and possible triggers.

Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) | Advice for Carers

Entering a new role as carer for a family member can be daunting. We cover some pratical suggestions, and have some useful carer support links and resources for you to access.

What is the advice surrounding vaccinations and Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS)?

Containing information on vaccinations via our Medical Advisory Board and sourced journals.

My child has been diagnosed with Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS)

Contains information on condition management, paediatric intensive care, how you can help, rehab, going home, and an indepth look at return to school.

Treatment for Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS) inc. ICU and help from you

Containing information on various treatments for GBS. We explore what may happen in the ICU (such as pain management and ventilation information) and how you can help someone with GBS during their stay (such as mental stimulation, keeping them calm, help coming off the ventilator).

Mental Health, Well Being, and Work following Guillain-Barré Syndrome (GBS)

Contains information on how to care for your mental health whether you’ve experienced GBS or a loved one had GBS. We discuss sexual relationships, before a section on returning to work – how to approach and talk to your employer after an absence.